Learning advocacy: five reflections after my summer internship

What is advocacy, what is it really?

I’d ask myself this every time I finished describing my summer internship at Generation Mental Health to my friends. I recognized the importance of the word on my tongue. Advocacy. Yet it felt elusive the more I thought about it, uncertain, and at times even, empty. Ad-vo-ca-cy, I’d repeat. To advocate, advocating, an advocate.

My Ukrainian parents didn’t seem to get the advocacy deal either, wholly confused by my talks of “defending” and “protecting” mental health—the best translations I could think of in Russian.

Defend mental health how? they probed.

Conflating advocacy with activism, I pictured myself carrying placards in crowded marches, only to remember that my main assignment this summer was to design a learning curriculum, and that my work would be entirely virtual. I’d have to figure it out soon, I knew, for my job not only required advocating, but also

teaching advocacy to others.

*

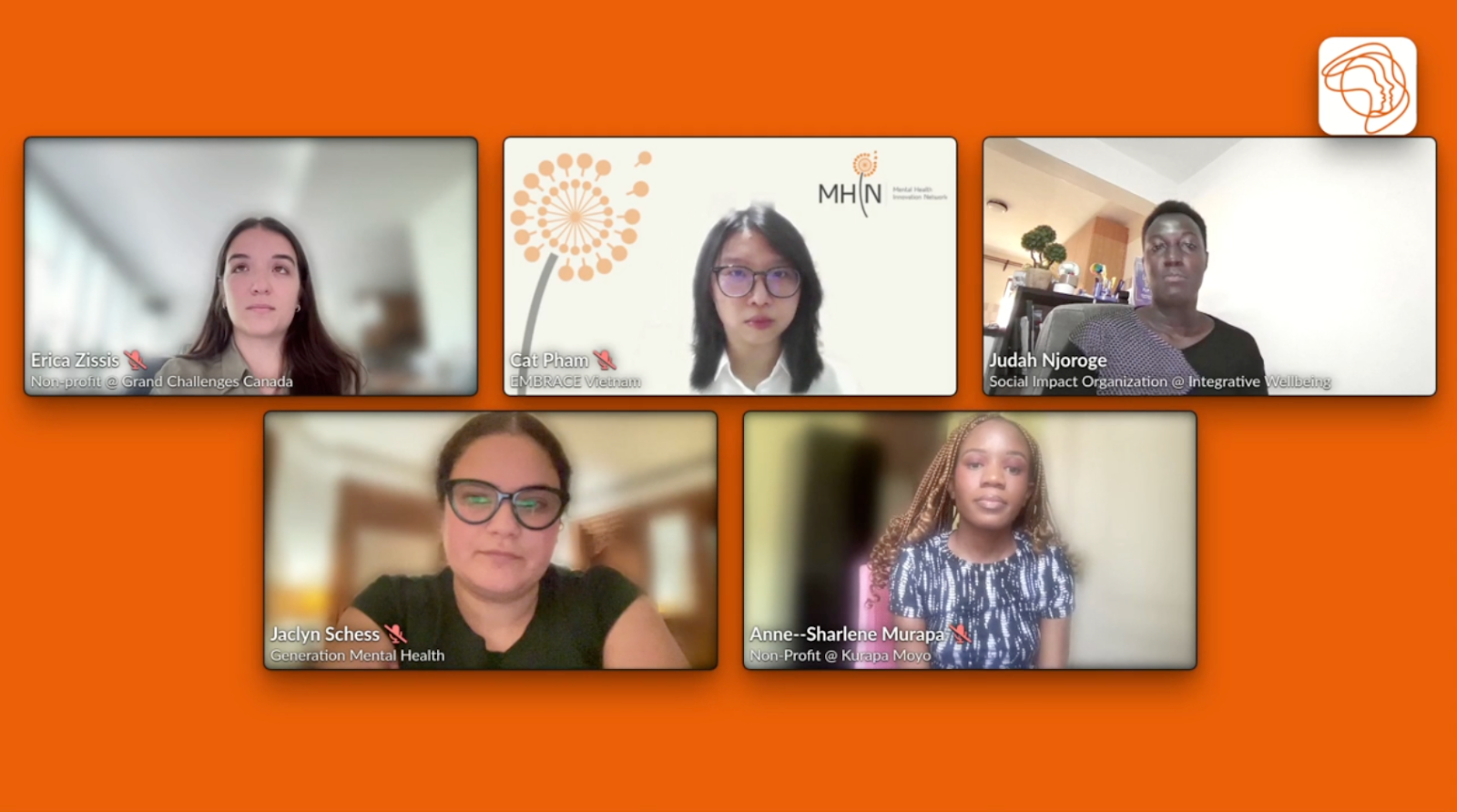

Twelve weeks later, I’m here, having spent the summer designing an advocacy course for youth, folks with lived experience, and community organizations interested in campaigning and awareness raising in mental health. I researched fascinating mental health advocacy and recovery programs around the world. I was able to personally connect with one of the founders of United for Global Mental Health, the first organization to campaign for mental health on a global scale, who is a GenMH team member. I had long conversations with my boss, a chemical engineer turned teacher turned advocate and psychologist-in-training, about striving toward linguistic diversity and the demand for services in Malayalam in southern India. I read about inspirational young people who are changing conversations about psychological wellness, and encountered distinct and equally radical approaches to organizing. In this time, I really started to grasp advocacy.

My early intuitions about advocacy weren’t wrong, but they were certainly incomplete; Advocacy, I’ve come to realize, doesn’t end at “defending” or “protecting” something, or using your platform and privilege to demand change. As I reflect on my internship at GenMH, I’ve been considering advocacy through these five frames:

Advocacy as education

A major part of advocacy is information sharing and resource distribution, whether that means educating others about current mental health legislation, designing informative toolkits, or making mental health knowledge accessible and organized via powerful search engines. Advocacy requires empowering others to act, connecting people, and fostering collaboration. Through fellowships and virtual courses, like the one I developed this summer, interested advocates and individuals with lived experience will gain research, outreach, and other essential capacity skills. Knowing my role as a young educator helped me increasingly see myself as a mental health advocate.

Advocacy as methodology

Researching, brainstorming, theorizing, sharing, and planning— these are only a handful of steps underlying the logic of advocacy. Once I familiarized myself with concepts like Theory of Change, stakeholder analysis, and needs analysis, I began appreciating the formulaic thinking that guides advocates and helps them ground, specify, and communicate their ideas. An advocacy mindset is honed through repetition and practice, answering hyperspecific questions, and always thinking ahead. Problem solving, my boss once told me, was the biggest similarity she identified between mechanical engineering and mental health advocacy.

Advocacy as voice

Beyond the elevator pitch, advocacy is an ask or a set of asks. It is also writing, emailing, petitioning, writing scripts, and telling stories— your story. Kind and inclusive language is important. For the lone advocate, vulnerable discussions in safe spaces are, too.

Advocacy as vision

I often think about what famous American Civil Rights activist Grace Lee Boggs said: “People are aware that they cannot continue in the same old way but are immobilized because they cannot imagine an alternative.” Advocacy is precisely this radical thinking and serious imagination, which prove so difficult, they render people imobile. When creating her infographic A Day In a Life: Imagining a Country without Racial Gaps, American storyteller Joanna Carrasco touches on the complexities of visionary thinking, in a blogpost: “I had trouble pushing myself to imagine what the most fruitful life … could even look like … It was difficult to imagine prosperity that is not often showcased or given attention.” Successful advocates are creative thinkers who keenly capture our world and incessantly strive to enact those visions of a better world.

Advocacy as the sum of small things

A late night email from our CEO, asking to reschedule our meeting because of insomnia and anxiety. A coworker sharing their struggles with vicarious trauma from this line of work. A postscript that begins with “In an effort to prioritise self care.” A supervisor reminding me they are always a WhatsApp call away. These tiny acts of honesty and self-advocacy are where we start.

written by Sarah Eisenberg, Generation Mental Health Summer Intern, 2022